Oppa

Oppa

“I was two tusks away from The Potato Fields,” grumbled Tolan. Tolan was always ‘two tusks away’ from a winning ‘wall’. Beldrynn had taken dozens of crescents from him in the week they’d been at sea. She felt kinda bad, but he kept coming back for more.

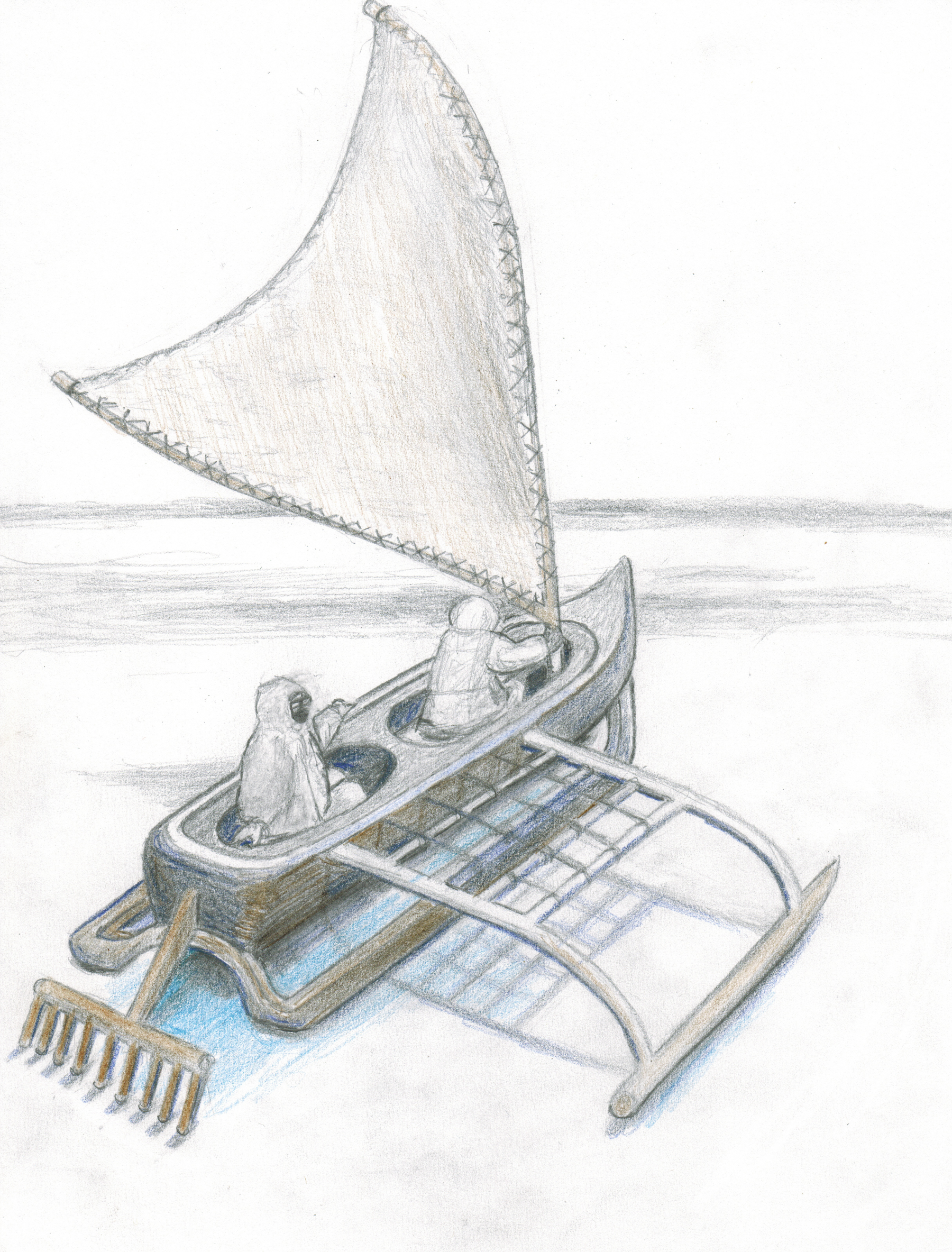

“Another round?” Bel was on a roll, today, and there was nothing else to do on this damn voyage. She’d been as surprised as the rest of the crew when Captain Brakeswan had told them that, instead of hunting whales, they were taking some rich weirdo to see the icebergs.

“You’ve taken enough coin from me,” Yahn said, gathering his meager pile of crescents, “and it’ll be dark soon. Notice how short the days are getting? We’ll be in the Winter Waters soon.”

“Aw, c’mon, Yahn, one more!” Tolan, ever the optimist, wanted to keep playing, but Yahn shook his head and Galdo agreed and started to gather up his tusks. It was a beautiful set, given to him by his grandfather, who had carved them himself. Galdo came from a long line of whale hunters, like Beldrynn, though none of her ancestors had much talent for scrimshaw. She’d grown up playing with far cruder sets and looked enviously at the smooth, evenly weighted tusks, with cleverly zigging edges that nested one to the next, as Galdo swept them into a battered leather-lined chest.

“I thought I’d never have to sail through that ice again.” They all knew what Bel meant. Whales weren’t as plentiful in the Inner Sea as they had once been. They’d all been on harrowing hunting trips through the northern sea ice, chasing the dwindling herds. The Winter Waters were terrifying and unpredictable, but they’d had three good seasons in the Inner Sea; Captain Brakeswan knew her stuff when it came to whaling grounds. They’d all been surprised when she’d accepted this charter.

Speculation about the identity of the strange young man who’d hired the ship carried the conversation for the next half hour, with the appropriate coin placed on the line to make it interesting. Tolan thought he was a noble kid ‘traveling the world’. Bel said she thought he was up to something, maybe bankrolled to scout for narwhals or a passage across the northern sea. Yahn thought he was a scholar bankrolled by nobles, “because he has a bunch of scrolls with him.” Galdo thought he’d heard someone say that Cordin was the guy’s great-great-grandfather, and a wizard carries scrolls too . . .

The Oppa, a hardy human folk, dwell in the far north. Once part of the Mena empire, they ventured east long ago and were eventually cut off from the rest of the Mena. The Oppa developed their own culture, over centuries, but retained some elements of Mena culture.

The Oppa once lived in Iza Mula and nearly as far south as Wurdonne. The orcs pushed them out of the mountains and the Gamaal later pushed them north. The Oppa long considered themselves “a people without a land”. Even their stronghold in the northeast was constantly threatened.

Government

The Oppa system of government is complicated. They have a king — currently a female, King Harianna — and a council of thanes, who are the heads of individual families or villages. They also have a council of citizens, chosen by election, and a council of elders. Each of these play multiple roles, not easily explained to outsiders.

The Oppa have survived countless clashes with the orcs of Iza Mula, known to be fiercer and far more hostile than the orcs of the Burkhdyn Gazar. For the last generation there has been tentative peace between the orcs and the Oppa, and even some trade. But the Oppa have a saying: “make peace, if possible, but expect war”. The younger generation train and spar as though they were headed off to battle at any moment. They are fearless and fearsome; matches nearly always result in bloodshed and too frequently result in serious — even permanent — injuries.

Commerce

Commerce

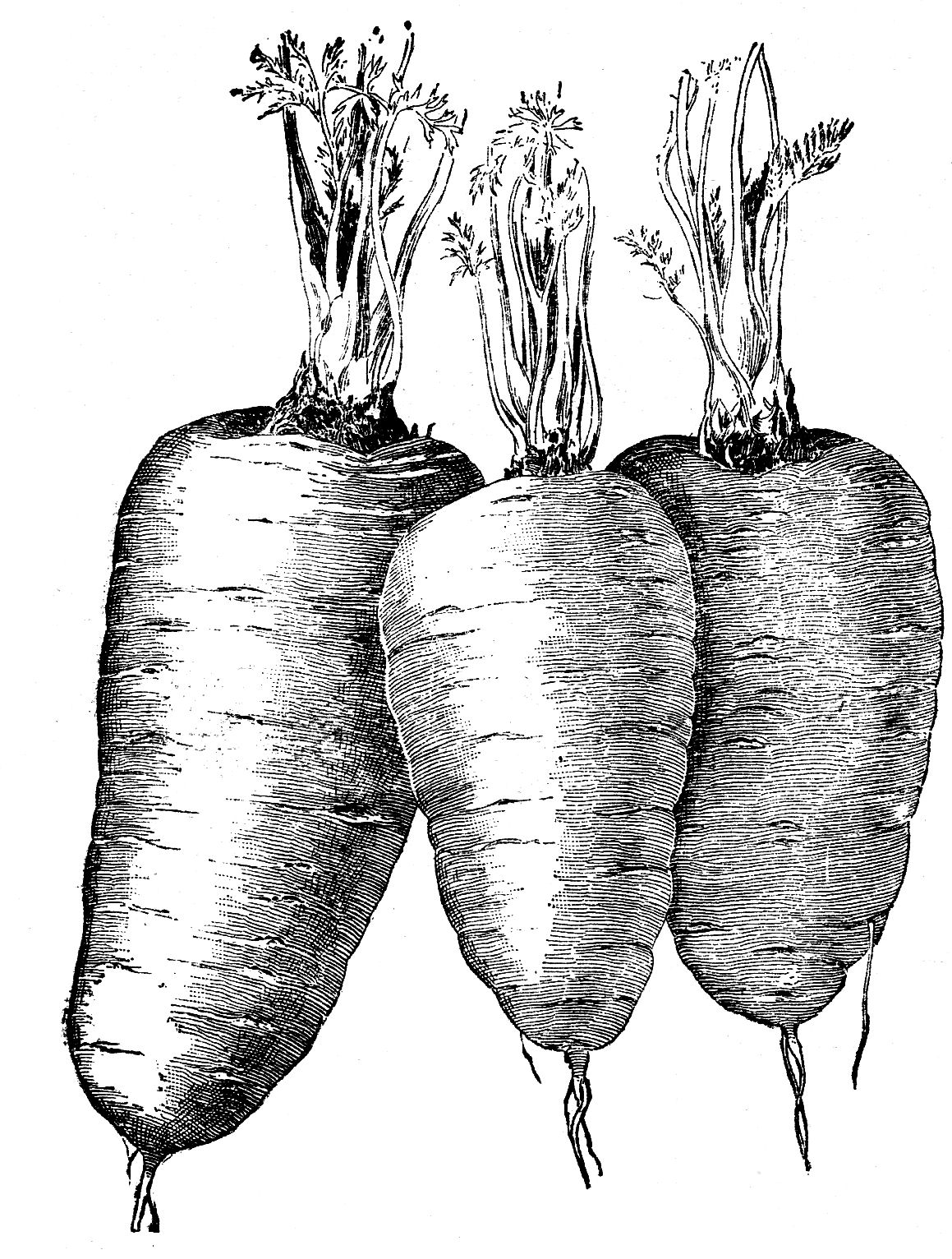

The Oppa are toughened by freezing climes and short growing seasons. They fish, hunt whales and mammoths, and somehow coax crops from their stark landscape. Their port city and capitol, Kelcarn, gives its name to Kelcarn carrots. The city, in turn, takes its name from the ancient cairns of boulder-sized stones on the high hill — or “kel” — above the city. The Oppa view this circle of stacked stone columns as sacred, connected both to their ancestors and the gods.

These folk are hard workers who rise with the sun. During the few months of long summer days they often work vigorously for 16 to 18 hours a day, ranging far from their homes. The dark winters bring a change to Oppa villages, as people are forced by darkness and weather to hunker down. During the dark months, Oppa train obsessively but also love to dance and tell tales of faeries and sprites.

“What’s your talent” is, roughly translated, the Oppa equivalent of “What do you do?” It is one of the first questions any Oppa will ask, because they have a caste system. The level of skill and of usefulness to the tribe accord higher status to certain talents than others. Some “talents” include hunting, fishing, herding, weaving, leatherworking, forging, scrimshaw, healing, prophecy, and bearing and caring for children. Those who don’t meaningfully contribute to their tribe can be banished. When asked “what is your talent?” it is inadvisable to respond, “I don’t know” or “I don’t have one”. Being evasive or secretive is also inadvisable. Every Oppa can name exactly what their talent, or role, is. They tend to be suspicious of people who “don’t know themselves.”

Culture and Entertainment

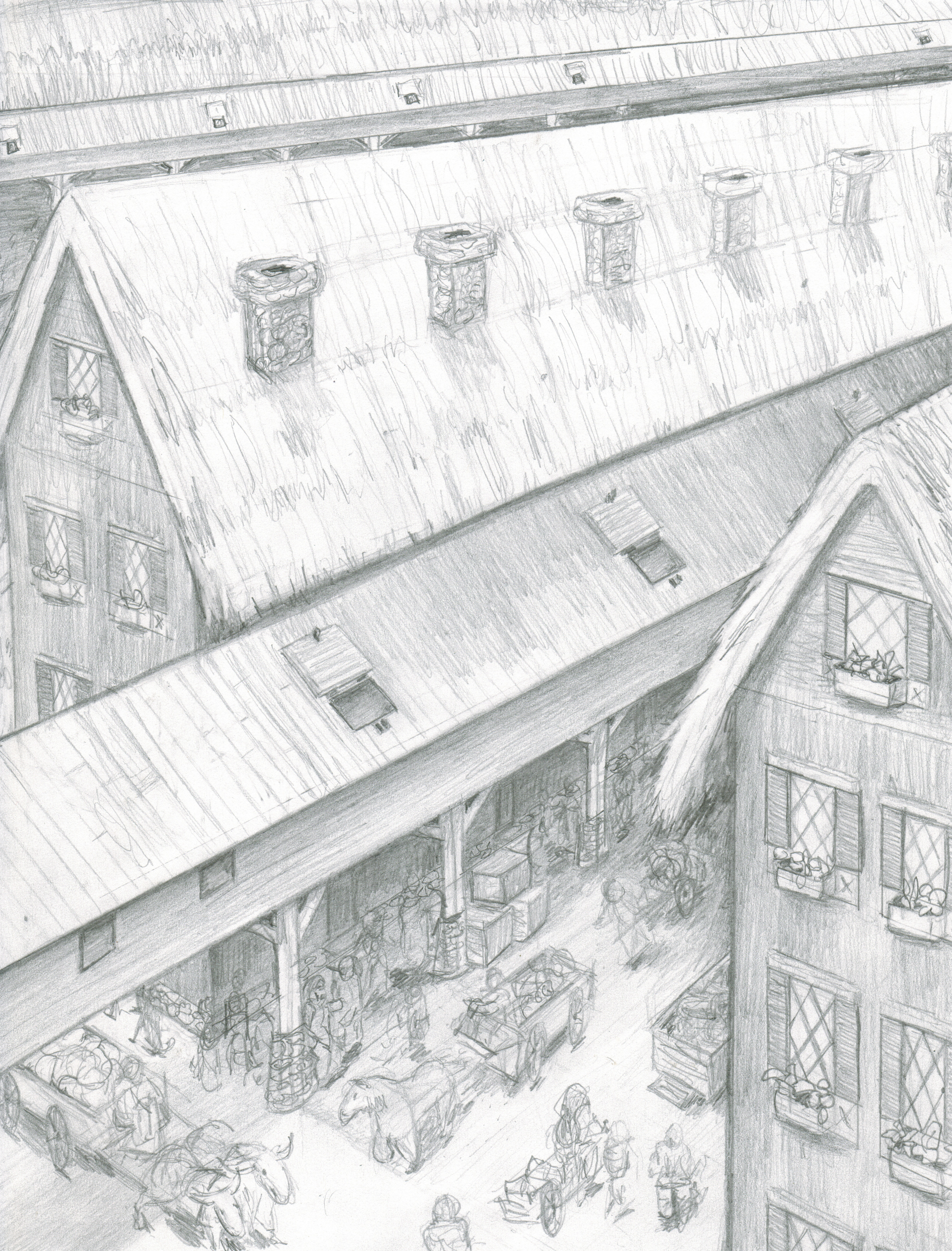

Oppa huts in Kelcarn are small and squat, built of local stones. Their thatched roofs are covered in large slate tiles that can bear the heavy weight of snow. Many are public houses, that serve stout ales and Oppa liquor, called vodka, which is made from the poisonous root called the “potato”. Though the Oppa seem to be immune to its toxins, this deceptively mild-smelling, clear liquor should be avoided at all costs by visitors! Nonetheless, these charming pubs are cozy rooms, always with a roaring fire in the stone fireplace, and the Oppa ale is surprisingly tasty.

Oppa huts in Kelcarn are small and squat, built of local stones. Their thatched roofs are covered in large slate tiles that can bear the heavy weight of snow. Many are public houses, that serve stout ales and Oppa liquor, called vodka, which is made from the poisonous root called the “potato”. Though the Oppa seem to be immune to its toxins, this deceptively mild-smelling, clear liquor should be avoided at all costs by visitors! Nonetheless, these charming pubs are cozy rooms, always with a roaring fire in the stone fireplace, and the Oppa ale is surprisingly tasty.

A few public houses also rent beds for the night, at very good prices. The price generally includes a filling Oppa breakfast of oat and barley flatbread topped with a fried duck egg and accompanied by thick shamba — a porridge of fish, greens, peas, turnips, leeks, carrots, and grains — that is reheated from the previous night’s dinner. Between the early breakfast and the evening meal, at sunset, the Oppa rarely eat. The best option for a hungry traveller during midday is to find a pub that serves fried cheese curds and fish. Only a handful do, but the cheese curds alone are worth experiencing.

The Oppa hairstyles, dress, and hygiene are very different from our own. Many have facial tattoos, usually in patterns of parallel lines or circles. Often, their forearms are similarly decorated. Oppa tend to wear the front sections of their hair pulled tightly back from the face and bound at the back of the head. This strangely severe style makes sense, as the frigid northern temperatures make hats a necessity much of the year. The Oppa hats are lined in fur and fit closely to the head, coming to a slight point on top. Some have wide leather straps that cover the ears and tie under the chin. Some cover the face and chin, leaving only the eyes exposed, with an opening at the nostrils for breathing.

The Oppa dress in layers; woven woolen shirts, leggings, and knee-length stockings are topped with felted wool tunics and leather pants. Over this, the Oppa add sleeved tunics, and — finally — fleece or fur coats and fur-lined boots. They often appear to be much larger than they are, mainly due to the layers and furs.

Religion and Customs

Most Oppa folk are friendly and welcoming, but disrespecting certain aspects of their culture can cause a pleasant encounter to take an ugly turn. Always take your boots off when you enter an Oppa home; to fail to do so indicates ill intentions. Never point your finger at an Oppa; they will think you are attempting to curse them. In fact, avoid pointing at anything, while in the company of Oppa. Never eat meat with your hands; use a knife or a piece of flatbread.

The Oppa way of cleansing is an adaptation to the cold northern clime. About once a moon they burn fragrant, clean woods that fill a special smoke hut with white smoke. They then strip naked and “bathe” in the smoke. Though several people may occupy the smoke hut, proper protocol is to keep silent and meditate or pray. More frequently, the Oppa use smokeless huts, heated by stoves to temperatures that rival the Doman deserts. These “saunas” are a more social activity and a good place to exchange news and gossip, while sweating away toxins and filth. As with the smoke huts, people enter the saunas bare. Both smoke huts and saunas are used by all citizens; the Oppa do not have taboos about mixed gender nudity. The Oppa regularly boil their underclothing and scrub their outer clothing with snow. Aside from the slightly tannic smell of woodsmoke, they are not an odoriferous people.

The Oppa way of cleansing is an adaptation to the cold northern clime. About once a moon they burn fragrant, clean woods that fill a special smoke hut with white smoke. They then strip naked and “bathe” in the smoke. Though several people may occupy the smoke hut, proper protocol is to keep silent and meditate or pray. More frequently, the Oppa use smokeless huts, heated by stoves to temperatures that rival the Doman deserts. These “saunas” are a more social activity and a good place to exchange news and gossip, while sweating away toxins and filth. As with the smoke huts, people enter the saunas bare. Both smoke huts and saunas are used by all citizens; the Oppa do not have taboos about mixed gender nudity. The Oppa regularly boil their underclothing and scrub their outer clothing with snow. Aside from the slightly tannic smell of woodsmoke, they are not an odoriferous people.

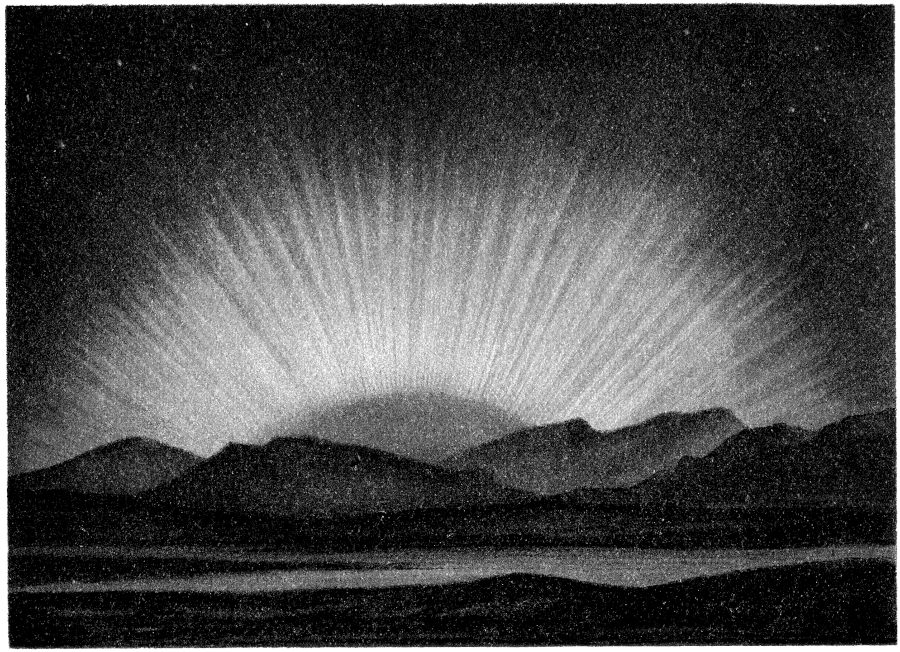

A week later, Beldrynn bid her friends goodnight after another hour of playing tusks. None of them had been able to concentrate or enjoy the games. They were far beyond merely sighting icebergs; the ice was closing in. Tolan, Yahn, and Galdo went below. Bel snuffed the lantern and sat alone in the dark, watching the stars. They were so bright and clear in these frigid waters. She wondered what it would be like to fly to the heavens, beyond where even birds could ascend. As if the gods were speaking to her, ripples of green and golden lights appeared in the sky, the famed Aurora. Beldrynn had made four previous trips into the Winter Waters, three on whaling vessels and one on an ice-harvesting ship, without ever seeing the Aurora.

It took her several minutes to notice that the skinny man who was paying for this voyage was standing at the bow of The Greyhorn, watching the dancing lights with his back to her. He was holding out a small ball of what looked to be glass, but was more likely ice, in the direction of the lights. His posture was bold, almost theatrical, and Bel couldn’t tell whether the thin, high, wail was coming from the man, the wind, or the Aurora. The wind was certainly picking up; in fact, a rogue gust suddenly tossed Bel to her knees on the deck. When she clambered to her feet the ship was still tossing. For a moment she thought the mysterious young man was gone, but then she noticed the golden green glow. It was coming from the small ball of ice in his hand. And then Bel realized: The Aurora was gone. Gone from the sky, anyway. It looked like Galdo was going to win those four sovereigns.